The Hidden Percentage

12.08.2022

Advocacy

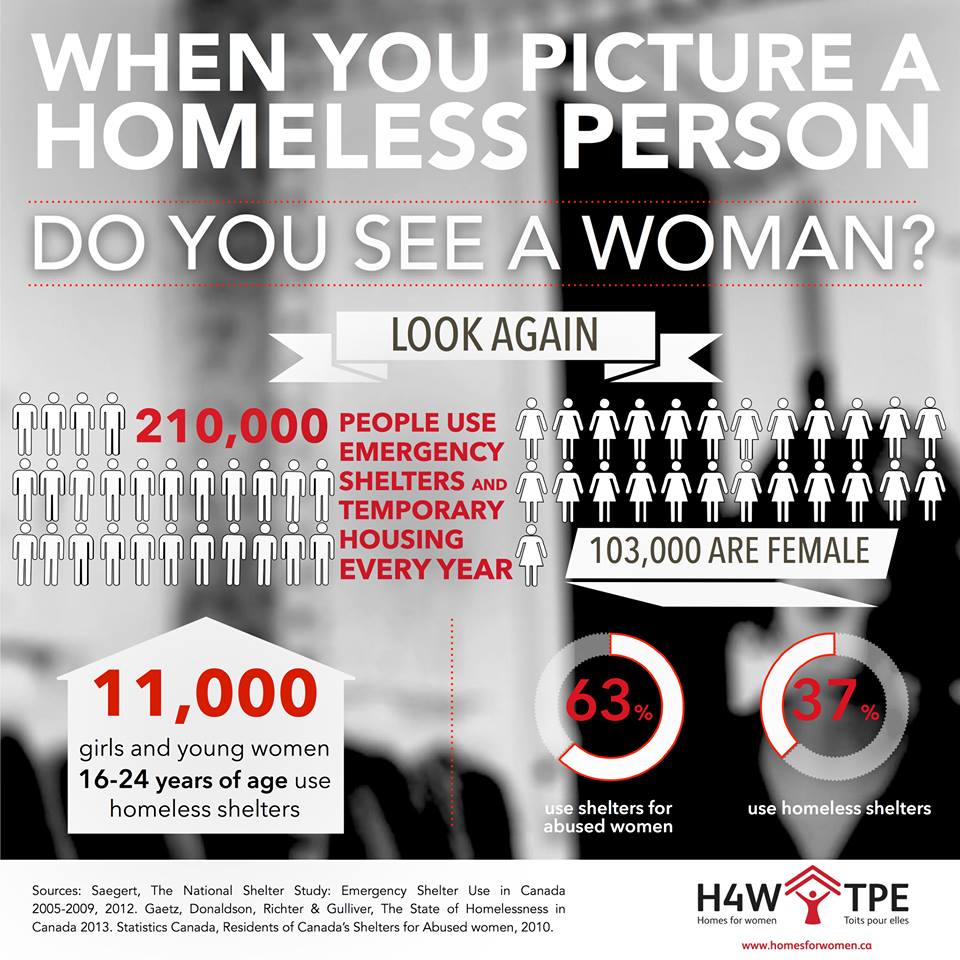

There are hundreds of studies, essays and web pages on homelessness in Canada. Most lack one thing though; they don’t address that homelessness and housing insecurity are often gendered experiences.

You may say, “well anyone can be homeless, how is gender involved?” This is not an uncommon response, especially as the studying of gender’s effect on homelessness is a relatively new concept.

Homelessness and housing insecurity are different for men than it is for women and gender-diverse people due to intersectionality. Intersectionality, coined by advocate Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, is the idea that social categorizations such as race, gender, and class are interconnected and thus create overlapping systems of discrimination. There may be support for women and there may be support for those experiencing homelessness, but there is a lack of support for women experiencing homelessness, even though these attributes affect each other. Not to mention support for women and gender-diverse people of colour or members of the 2SLGBTQ+ community.

Studies have shown that homelessness and housing insecurity for women and gender-diverse people is drastically different than for men but there is a lack of resources specifically for them. It was found that 68% of all shelter beds are designated as co-ed, or for male-identified people, while 38% of all shelter beds are open to all genders, and only 13% of all shelter beds are dedicated specifically to women (Schwan, Vaccaro, Reid, & Baig, 2021). Women and gender-diverse people may avoid co-ed shelters due to trauma or past negative experiences.

Women are more likely to experience poverty as well (Angus Reid Institute, 2018). This can be attributed to the gender wage gap and the disproportionate amount of unpaid work, such as child care and housework, that women are expected to take on which gives them less time for paid work (Fletcher & McWhinney, 2019). Being at a higher risk of poverty thus puts women at a higher risk of homelessness, yet there is a lack of women and gender-diverse specific supports for those experiencing homelessness.

Hidden Homelessness

Women and gender-diverse people are more likely to experience hidden homelessness as well. But was is hidden homelessness?

Researchers and experts have outlined two main types of homelessness: absolute homelessness and hidden homelessness (Gaetz, et al., 2017).

Absolute homelessness is the type of homelessness that we can see. It is visually seen as displaced people in our communities, or in places not meant for housing such as empty commercial buildings.

Hidden homelessness is the type of homelessness that can appear invisible to the public. Those experiencing hidden homelessness usually don’t access support and often “couch surf” or sleep in their car. Due to them not accessing support, people experiencing hidden homelessness are left out of official counts, making statistics underestimates. Women and gender-diverse people are more likely to experience hidden homeless for many reasons (Canadian Alliance to End Homelessness, 2021).

These reasons include but are not limited to:

– Fear of violent victimization if on the street.

– Turned away from women’s shelters due to overcrowding.

– Avoid co-ed shelters due to past traumas or fears.

– Fear of having children taken away by family services if reported by the shelter.

– Stigma of homelessness.

Hidden homelessness amongst women and gender-diverse people is an epidemic and requires observation through an intersectional lens to best assess the situation.

What is the answer?

There is no singular answer because homelessness is not a static experience; it is fluid and different for everyone. There may not be one answer, but there are steps we can take as recommended by experts, to better address the issue of intersectionality in homelessness.

The first recommendation is to listen to the women and gender-diverse people experiencing homelessness. No one knows better what they need than themselves.

Next is to look at homelessness through an intersectional lens and understand how gender influences it. Once we as a society acknowledge that the experience of homelessness is not the same for everyone and things like gender, sexuality, and race play a part, we can go forward to better understand the topic.

Another step is to consider topics such as gender when researching homelessness. There is a lack of research on the intersectionality of homelessness and most surveys don’t account for gender, making it difficult to understand the full scope of the issue.

In conclusion, the gendered homelessness epidemic is not hopeless. Once we acknowledge the effect gender has on homelessness we can begin to better understand the issue and take steps to address it on a local and national level.

References

Angus Reid Institute. (2018, July 17). What does poverty look like in Canada? Survey finds one-in-four experience notable economic hardship. Retrieved from Angus Reid Institute: https://angusreid.org/poverty-in-canada/

Auffrey, M., Tutty, L. M., & Wright, A. (2017). Preventing homelessness for women who leave abusive partners: A shelter-based “Housing First” program. Innovations in interventions to address intimate partner violence: Research and Practice.

Canadian Alliance to End Homelessness. (2021, July 27). Women’s homelessness: hidden in plain sight. Retrieved from Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation : https://www.cmhc-schl.gc.ca/en/nhs/nhs-project-profiles/2018-nhs-projects/womens-homelessness-hidden-plain-sight#:~:text=Women%20are%20more%20likely%20to,are%20frequently%20operating%20over%20capacity.

Canadian Women’s Foundation. (2022, June 1). The Facts About Sexual Assault and Harassment. Retrieved from Canadian Women’s Foundation: https://canadianwomen.org/the-facts/sexual-assault-harassment/

Fletcher, A. J., & McWhinney, T. (2019). Surveying Policy Priorities: The Saskatchewan Women’s Issue Study.

Gaetz, S., Barr, C., Friesen, A., Harris, B., Pauly, B., Pearce, B., . . . Marsolais, A. (2017). Canadian Definition of Homelessness. Toronto: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness.

Homeless Hub. (n.d.). Hidden Homelessness. Retrieved from Homeless Hub: https://www.homelesshub.ca/about-homelessness/population-specific/hidden-homelessness#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20Canadian%20Definition,prospects%20for%20accessing%20permanent%20housing.%E2%80%9D

Patek, R. (2020, April 27). Minister says COVID-19 is empowering domestic violence abusers as rates rise in parts of Canada. Retrieved from CBC News: https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/domestic-violence-rates-rising-due-to-covid19-1.5545851

Schwan, K., Vaccaro, M.-E., Reid, L., & Baig, K. (2021). The Pan-Canadian Women’s Housing and Homelessness Survey. Toronto, ON: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness.